The Donation Miracle

March 12, 2019

Although the odds of winning the lottery are small, people buy tickets because hitting the jackpot would be worth it. Like ambitious ticket buyers, thousands of people register with The National Bone Marrow Program (NBMP), also known as Be the Match, even though the chances of matching a recipient in need are as unlikely as hitting the jackpot. Some donors enter in hopes of a miracle, like family members, but others register in the spur of the moment thinking they will never get called. However, much like the lottery, these people are needed too. You never know who might have the winning ticket.

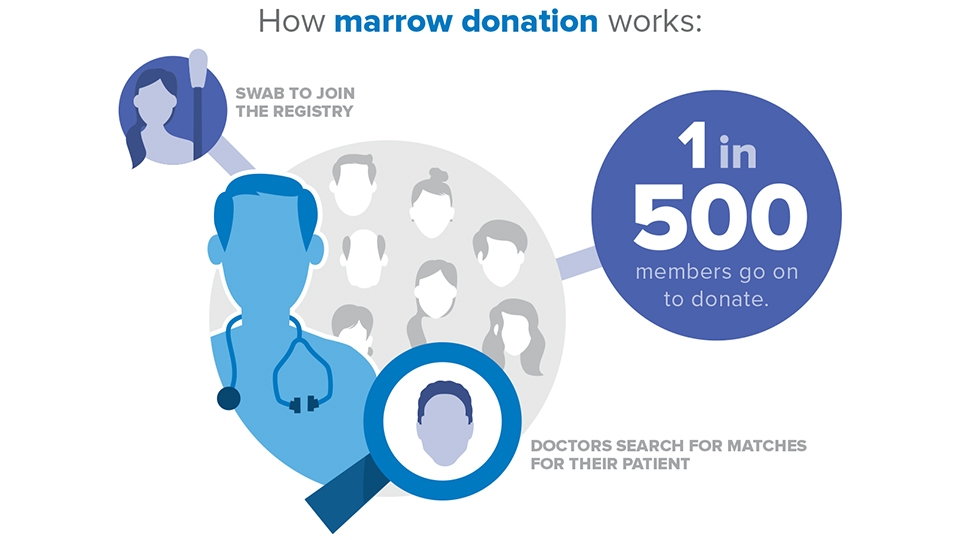

Leukemia, cancer of the marrow and blood, is the second leading cause of cancer death among children, adolescents and young adults under 20 years old. Acute myelocytic leukemia (AML), a rare form of leukemia mostly common in adults, is found among about 500 children in the USA each year (St. Jude Children’s Hospital). Although chemotherapy is the standard  treatment, if children are at high risk of relapse or resistant to treatments, they can receive a bone marrow transplant (St. Jude Children’s Hospital). This transplant uses a donor’s blood or bone marrow to replace blood cells that may have been killed by chemo and/or radiation therapy with healthy blood cells (St. Jude Children’s Hospital). In order to get the transplant, the donor must match the patient, and matches are hard to find. 30 percent of bone marrow patients in need of transplants have matching donors in their families, but the other 70 percent hope to find donors through the national registry for unrelated donors to save their lives (Institute for Justice). At any given time, 7,500 Americans are searching for unrelated donors through the national registry (Institute for Justice). But only two percent of population is on the national registry, so there is not a large pool from which to choose (Institute for Justice). However, miracles happen through the NBMP, such as for Louise Hindal, the Upper School Technology Coordinator at Charlotte Latin School, and Jordan Jemsek, currently an eighth grade student at Charlotte Latin School.

treatment, if children are at high risk of relapse or resistant to treatments, they can receive a bone marrow transplant (St. Jude Children’s Hospital). This transplant uses a donor’s blood or bone marrow to replace blood cells that may have been killed by chemo and/or radiation therapy with healthy blood cells (St. Jude Children’s Hospital). In order to get the transplant, the donor must match the patient, and matches are hard to find. 30 percent of bone marrow patients in need of transplants have matching donors in their families, but the other 70 percent hope to find donors through the national registry for unrelated donors to save their lives (Institute for Justice). At any given time, 7,500 Americans are searching for unrelated donors through the national registry (Institute for Justice). But only two percent of population is on the national registry, so there is not a large pool from which to choose (Institute for Justice). However, miracles happen through the NBMP, such as for Louise Hindal, the Upper School Technology Coordinator at Charlotte Latin School, and Jordan Jemsek, currently an eighth grade student at Charlotte Latin School.

Jordan was diagnosed with acute myelocytic leukemia in August of 2009 when she was five years old. This devastating news came at an unfortunate time as her grandmother had just passed away from ovarian cancer and her mother had just been diagnosed with breast cancer. She received treatment until she was in remission in Easter of 2010.

Those seven months were difficult; Jordan remembers, “just sitting in bed and doing nothing all the time is what

irritated me the most.” Jordan’s mother, Kay Jemsek, helped her through the fight. “She had such a good disposition, was such an upbeat funny kid that it probably saved her life,” Kay said. Kay was by her side at Novant Health Presbyterian Hospital as they both received treatment. She insisted on having a bed next to her daughter so she “could take care of her and go down and get radiation and come back up and stay beside each other.” Jordan remembers going down to where her mother was getting radiation. She recalls, “they let me speak to her one day” by having her talk into a microphone. In the hospital, “her view was of a brick wall, so she couldn’t see the sun or clouds or anything. But she had a checklist of things she wanted to do when she got out of the hospital,” Kay said. ‘“I want to walk on the beach, I want to see a sunset, I want a dog.’”

Her strength, hope, and support of her mother helped her fight until Easter of 2010 when she was in remission, but sadly, she relapsed in November.

At this point, Jordan needed a transplant to save her life. Although family members are typically the most ideal matches for donations, no one in Jordan’s family matched. News started circulating about Jordan in order to get the word out in hopes of finding a match. Bobby Labonte, a famous NASCAR driver, was so moved by an article in “The Charlotte Observer” on Jordan that he promoted a bone marrow drive in her honor on March 5. He also featured a picture of Jordan on the back of his No. 47 Camry and the URL “www.getswabbed.org” to promote the marrow drive. In honor of Jordan, 768 people attended the blood marrow drive held at St. Gabriel Catholic Church. People got swabbed and became part of the national bone marrow registry. A speech handle picked up on Jordan’s story and asked to interview Kay, Jordan, Bobby, and the race car team. “3-6 million people would see that,” Kay said. News was spreading as quickly as Jordan’s cancer in her body, and her need for a donor became more and more urgent.

Louise, a student at Harvard University from Charlotte, was volunteering at a cancer fundraising event called 24 Hours of Booty in the last weekend of July. She had been volunteering at the Packet Pickup tent, but the tent next to hers was the NBMP tent. “I sat there for so many hours listening to ‘you could save a life by signing up, all it requires is a cheek swab, you may not get called forever but you might get called,’” Louise said. She had never heard about it before, “but they made a good case and talked about how much of an impact you can have by signing up, so I did it. I figured I may never get called, I may get called 20 years from now, I don’t know.”

In the spring of her junior year, the NMDP left a voicemail at her home in Charlotte that she was a match. “I was surprised and kind of nervous, but thought it was a really cool, amazing opportunity,” Louise said. She followed the next steps to do more testing, get blood drawn and eventually it came back that she was indeed the best possible match. All they can tell a donor about the recipient is the age, gender and disease, so all Louise knew was that she was the best possible match for a six-year-old girl with leukemia. The doctors told Louise that the patient’s leukemia was aggressive and they wanted to proceed as quickly as possible. “As they talked about the surgery, there were a couple of times like, do I really want to do this, there is some risk. But those moments were very brief because the risks weren’t that big with the knowledge that I could save a six-year-old’s life,” Louise said.

It was a quick turn around for Louise. After learning that she was the match in February of 2011, she donated on March 16. To have the support of her mother, she went back to her North Carolina home to have the surgery. “I had never had surgery before so I was pretty nervous about it,” Louise said. The procedure required general anesthesia, 4 holes drilled into her pelvis to extract the marrow and then a couple of stitches. “The worst thing I remember about that day was just being nauseous from the painkillers they gave me, but they gave me anti-nausea meds to take care of that,” Louise said. She was allowed to go home that evening and had soreness the next couple of days. “It hurt to sit in some ways, to lie down in some ways, but nothing bad. I was taking ibuprofen,” Louise said. Her closest friends and family knew about it, but Louise didn’t talk about it much. “I was very proud but it also seemed kind of personal for me and the recipient, who I didn’t know at the time,” Louise said.

Meanwhile, Jordan Jemsek was preparing to receive Louise’s bone marrow. The news of having a donor struck Jordan’s family. “I was just so grateful, you just pray for it, like this is the person that is going to save my daughter’s life,” Kay said. She went into the Children’s National – Main Hospital in DC in February of 2011 where she remained for four months for the bone marrow transplant. In the leading days up to the recipient getting the bone marrow, the patient goes through a rigorous treatment to kill the bone marrow. This “was probably the worst part of everything—she was so sick. And they won’t let you eat. She got so emaciated and skinny,” Kay said. Although she was hungry, Jordan could only get food through a vein. At this point, she was so sick, “I thought I was going to lose her,” Kay said. “I just remember calling my friends and saying, ‘you just got to pray for my daughter; she is not doing well.” Unlike Presbyterian, this hospital would not allow Kay to have a bed next to Jordan because they told her that “a lot of our patients code,” and they needed to make sure they could get to Jordan. But Kay was so attentive to her daughter that she slept on an air mattress next to her for those four months. Jordan’s treatments had taken a tremendous toll on her body and “as a little kid, you can only take so much. But she did really well, she’s a tough cookie,” Kay said.

Jordan Jemsek got the transplant on March 17. Louise had seen Jordan Jemsek in “The Charlotte Observer” in February and around that the time, she found out that she was a match for a six-year-old-girl with leukemia. “My mom had said, ‘maybe you’re her donor.’” Then, on March 17, the day after Louise donated, a new “Charlotte Observer” article came out saying that Jordan Jemsek had received a transplant. “At that point, my mom and I were like, this has to be her. She was the right age, she had the right disease, and she got the donation the day after I donated. Even if it wasn’t her, we were just going to adopt it as if it was her; in my head, she’s going to be the person that I donated to,” Louise said. After not actually finding out who the donor was for about a year, the NBMP reached out to the Jemseks asking if they would like to exchange information. When they said yes, Louise found out that it was indeed Jordan Jemsek. Not only are they both from Charlotte, but Jordan’s brother attended the same school, Charlotte Latin School, at the time as Louise did. They met in 2013 when Jordan was eight-years-old and a news story captured them together. Jordan and Louise being from the same city is astronomical.

Now, “my life is great,” Jordan said. Jordan just turned 14, plays lacrosse, takes honors geometry and advanced conceptual physics, gets good grades, has great friends, and loves her teachers. Jordan Jemsek doesn’t talk about her experience often because she does not want to be known as the “cancer kid,” as Kay said, but some of her friends know. Jordan remembers, “in humanities class, my teacher said, ‘I used to have a girl who had cancer in my class,’ without even knowing I had it. My two friends in the class that knew about it looked at me and we started dying laughing, but no one else knew.” She also remembers her science teacher asking her to explain it to the class. Other than her closest friends and that science class, most of her peers at school don’t know. “My friends said that if I ever relapse again, they’re going to shave their heads,” Jordan said. But now, Jordan’s life is back to normal. “You’d think that cancer would be something that you think about everyday, but I don’t. For now, I give myself shots everyday with growth hormones because chemo messed with my thyroid and I have to take a pill every night. But, really, it’s just normal,” Jordan said. Yet people still remind her of her inspiration and effect on the community. “At a Panthers’ game, a police officer tapped Jordan on the shoulder and said, ‘Are you Jordan Jemsek? My church prayed for you’,” Kay said.

Louise is living happily and healthily as well. Her longest lasting repercussion was a drop in iron because of the fluid taken from her, so she would get winded from walking up the stairs. But, “after a month, I was pretty much back to normal. The cuts themselves healed pretty quickly; they were gone a week later at most,” she said. Like for Jordan, it does not come up often. “I think about it every year on March 16,” she said.

Although they live separate lives, they are still tightly connected to each other. Not only through the bone marrow, but because Jordan attends the same school that Louise teaches. “Very often, donations are international, and it just so happened that we live 10 minutes from each other,” Louise said. Louise actually taught Jordan’s brother and was his advisor. Although close in proximity, Jordan and Louise don’t interact frequently. “I saw her last year for the first time in awhile and walked passed her and was like ‘oh, that’s Jordan!’ But she’s not a little kid anymore, now she’s a young adult!” Jordan wishes they talked more. “I don’t know where she teaches in the building. It’s crazy enough it’s the same school. I don’t know why I never see her!” Jordan said. But if Jordan decides to take computer science in Upper School, Hindal could be her teacher. For now, “it’s just cool to know that my bone marrow is growing in the Middle School too, inside of Jordan!” Louise said.

Jordan’s story has inspired and encouraged many people to donate. In honor of Jordan, three other people donated their bone marrow and saved someone else in need because they were so touched by her story. Her science teacher became a donor because of the inspiration she sparked when explaining cancer to the class.

“There are police officers and firemen who can save lives every day. But there are not opportunities where you as a person can totally and completely save someone’s life, where you can give this amazing gift in the world and save somebody, and a lot of times a child,” Kay said.

Through entering the registry, miracles happen. As the NBMP told Kay, “the chances of the donor and recipient being from the same state are astronomical; the same city is like winning the lottery.”

Go enter the registry. You may just win the jackpot.

Sources:

https://www.lls.org/http%3A/llsorg.prod.acquia-sites.com/facts-and-statistics/facts-and-statistics-overview/facts-and-statistics/childhood-blood-cancer-facts-and-statistics#Leukemia

https://www.stjude.org/disease/acute-myeloid-leukemia.html

https://www.nhms.com/about/headlines/nascar/girl-needs-marrow-transplant-labonte-wants-help.html

https://ij.org/bonemarrowstatistics/